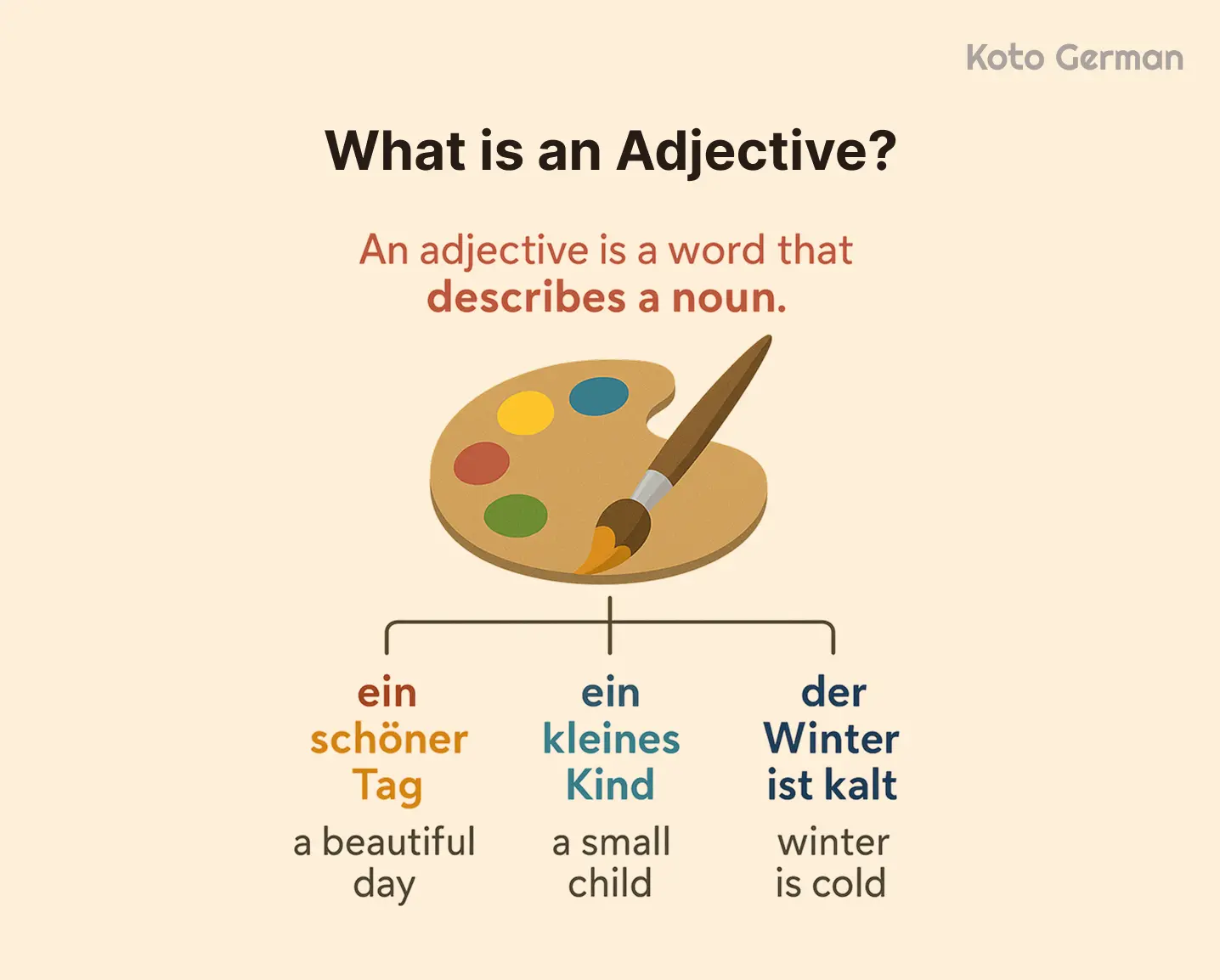

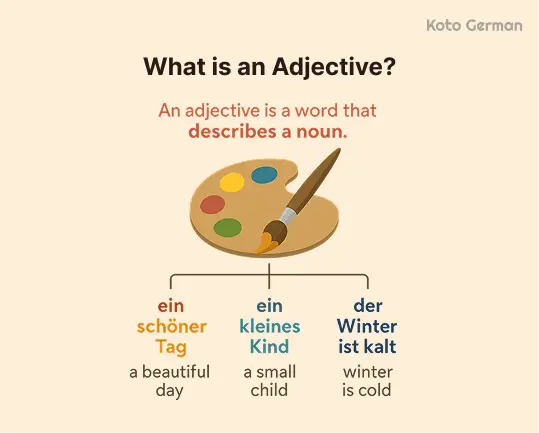

What is a German Adjective?

Adjectives are the seasoning to any language, coloring nouns in terms of size, mood or character. In your own words, they say more about the thing we are discussing — a nice neighbor, a large house, or a fine day.

Common adjectives in German pull double duty: they not only describe but also dance to the beat of grammar. They must match the gender (masculine, feminine, neuter), case (nominative, accusative, dative, genitive), and number (singular or plural) of the noun they’re tagging along with. This “chameleon-like” ability means their endings change depending on the sentence’s setup.

Take schön (beautiful), groß (big), or freundlich (friendly) as examples. In ein schöner Tag (“a beautiful day”), the adjective schön shifts to schöner to fit the masculine, singular, nominative noun Tag. Mastering these little shape-shifters is like learning the secret handshake of German grammar — they make your sentences click and feel effortlessly natural.

Level up your German with Koto!

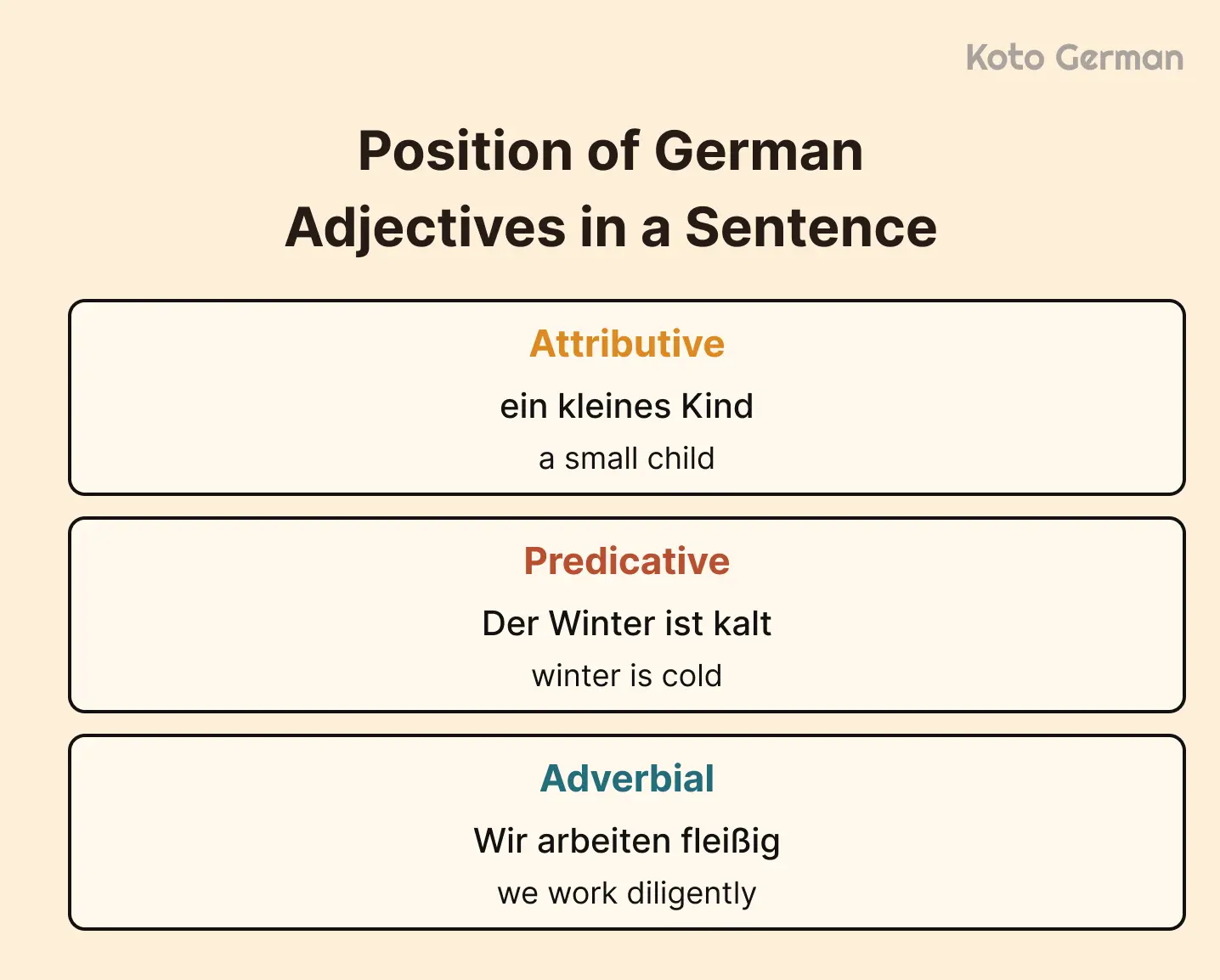

Position of German Adjectives in a Sentence

In German, adjectives follow clear patterns instead of floating around at random. Their role depends on their position in the sentence, and this position also determines their form.

Sometimes they stand before a noun and take specific endings, sometimes they link to the subject through a verb, and sometimes they describe how an action is carried out. These three functions are called attributive, predicative, and adverbial use.

Attributive Adjectives – Before the Noun

When an adjective comes directly before a noun, it’s in its attributive position. Here, it takes on special endings to match the noun’s gender, case, and number. These endings are non-negotiable — it’s the German way of making sure the adjective and noun are perfectly in sync.

Example: ein

The adjective klein becomes kleines because Kind is neuter, singular, and nominative. In attributive form, adjectives serve as accessories, completing the noun’s style with the right grammatical ending. For reference, adjectives in German list can help you see patterns, compare endings, and find common descriptive words for everyday use.

Predicative Adjectives – After the Verb

Predicative adjectives show up after certain verbs, most often sein (to be), werden (to become), and bleiben (to stay). In this role, they’re describing the subject, but they don’t take endings. They keep their base form, almost like they’re off-duty and don’t have to wear a uniform.

Example: der Winter ist

Kalt stays simple, with no endings. It’s pure essence, no grammatical accessories needed.

Adverbial Adjectives – Modifying Verbs

Sometimes, even basic German adjectives step out of the noun world entirely and start modifying verbs. In this adverbial role, they describe how something is done, not what something is. Again, no endings are needed — they stay in their plain form.

Example: Wir arbeiten

Here, fleißig describes the way we work. Adverbial adjectives highlight the how of the action and stay in the shadows of the verb.

Knowing where your adjective sits in a sentence changes how you treat it. Put it before a noun, and it needs endings. Place it after a verb like sein, and it stays in its natural state. Use it to modify a verb, and you’re in adverbial territory, again with no endings.

You’ll see how German adjectives follow precise rules after you gain a sense of their positions; it’s similar to studying the dance’s choreography. You might miss a step or two at first, but you’ll soon be able to go through sentences effortlessly and nail each beat precisely.

Rules for Using an Adjective in German

Despite their small appearance on paper, adjectives have a lot of meaning in German. Depending on where they appear and what they’re describing, they can adapt, modify, and even fully transform in addition to describing nouns.

Every learner should be aware of a few golden guidelines in order to use them properly.

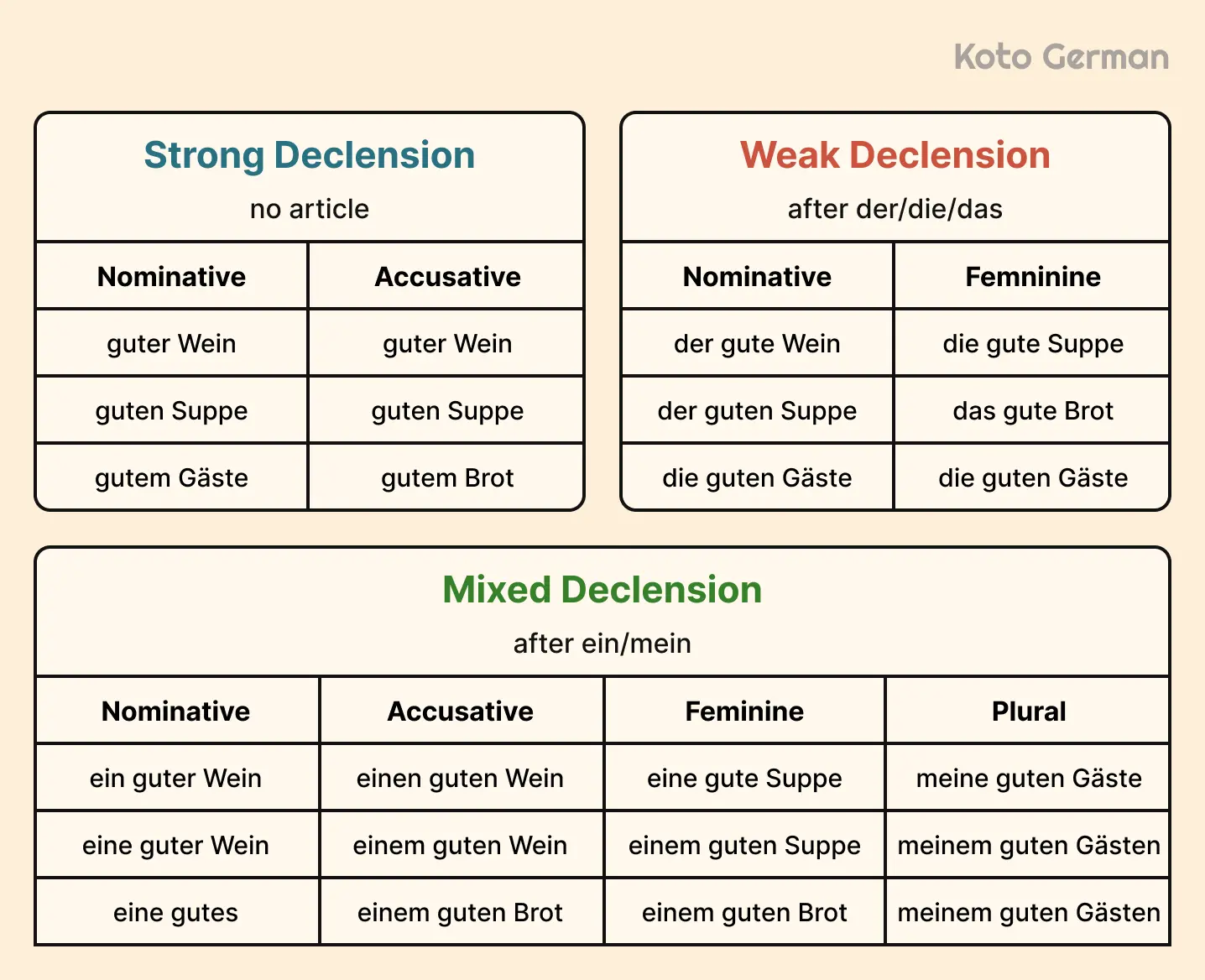

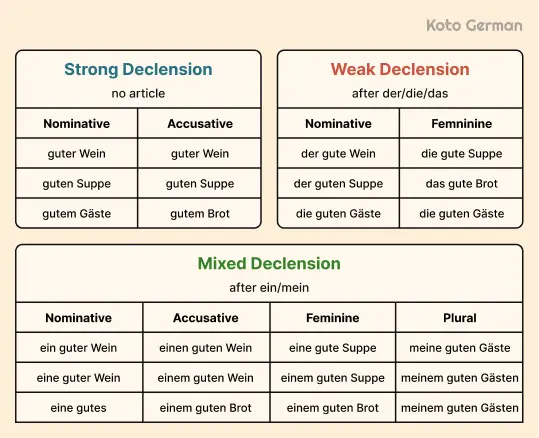

Strong Declension

Strong declension steps in when there’s no article before the common German adjectives. In this case, the adjective has to do all the heavy lifting. It carries the full information about case, gender, and number.

| Case | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | -er | -e | -es | -e |

| Accusative | -en | -e | -es | -e |

| Dative | -em | -er | -em | -en |

| Genitive | -en | -er | -en | -er |

Strong endings make sure the listener immediately knows what kind of noun is being described, even without an article. Think of it as the adjective wearing a bright neon sign that says, “Here’s the gender and case!”

Strong declension = no article → the adjective carries all the grammatical information (gender, case, number).

Weak Declension

Weak declension comes into play after definite articles (der, die, das) or similar words like jeder (each) or welcher (which). Since the article already signals gender, case, and number, the adjective can take it easy and wear “weaker” endings, usually -e or -en.

A list of adjectives in German can be useful to practice which adjectives commonly appear with weak declension and help you remember the endings more easily.

| Case | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | -e | -e | -e | -en |

| Accusative | -en | -e | -e | -en |

| Dative | -en | -en | -en | -en |

| Genitive | -en | -en | -en | -en |

Here, the definite article does most of the talking, so the adjective just follows along politely.

Weak declension = after der/die/das or similar (jeder, welcher) → the article already gives the info, the adjective just takes the “weak” ending (-e or -en).

Mixed Declension

Mixed declension appears after indefinite articles (ein, eine) and possessive pronouns (mein, dein, unser). These words give only partial information about gender, case, or number. The adjective then has to pick up the slack. Its endings are a hybrid of strong and weak patterns, hence the name “mixed.”

| Case | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | -er | -e | -es | -en |

| Accusative | -en | -e | -es | -en |

| Dative | -en | -en | -en | -en |

| Genitive | -en | -en | -en | -en |

Mixed declension is teamwork in action: the article shows some details, and the adjective fills in the rest.

Mixed declension = after ein/eine, mein/dein/unser etc. → the article gives part of the info, the adjective fills in the rest.

German adjective endings can feel tricky initially, but the declension rules provide structure. Strong declension emphasizes the adjective, weak declension relies on the article, and mixed declension combines both. Using a list of German adjectives makes it easier to see which endings fit each case.

As soon as you train yourself with everyday words like interessanter Film, neue Schuhe, frische Blumen, schnelle Züge, the system ceases to be a puzzle and becomes second nature.

Adjectives aren’t just decoration in German; they’re grammar partners, guiding the reader or listener through the sentence with precision.

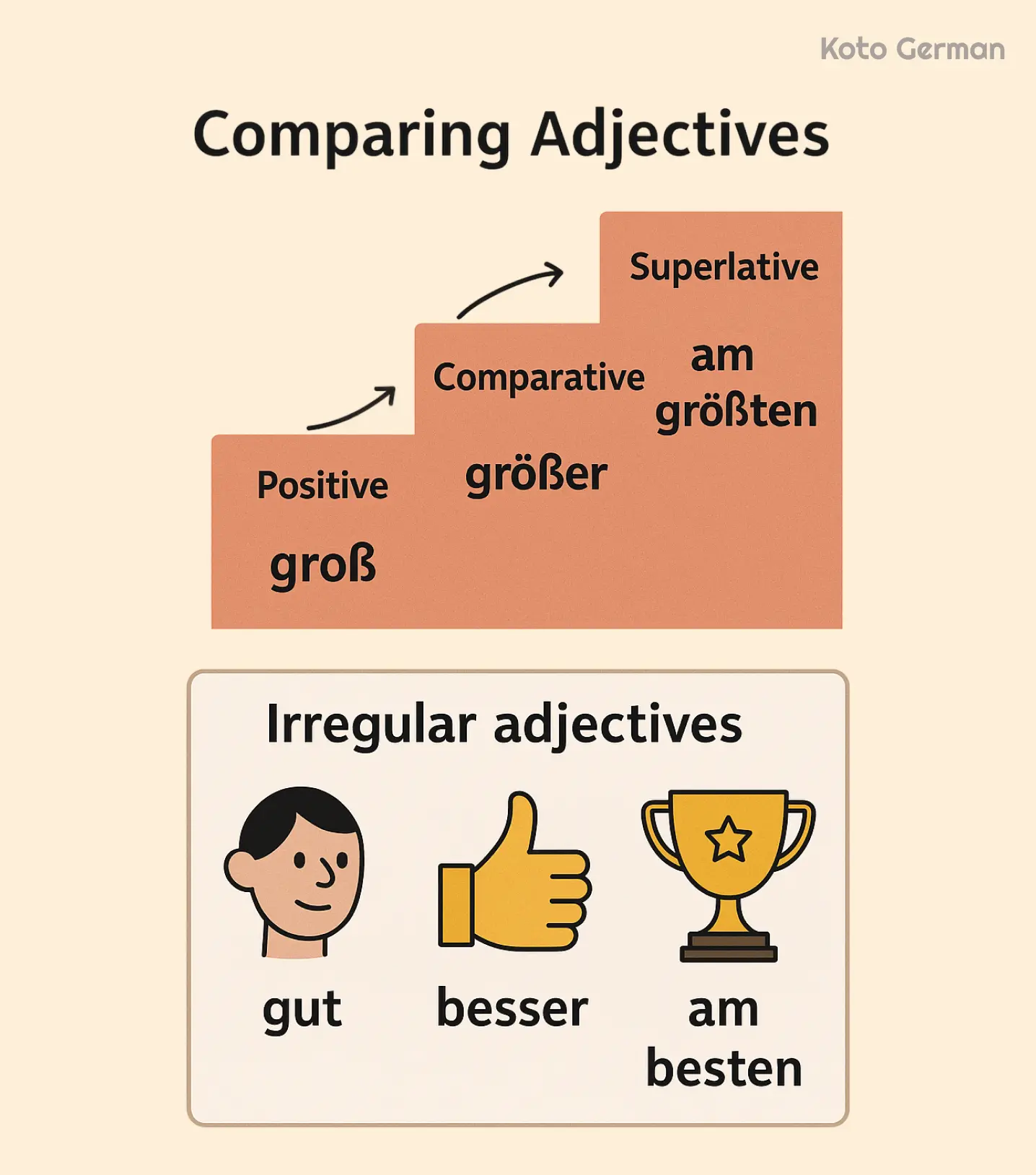

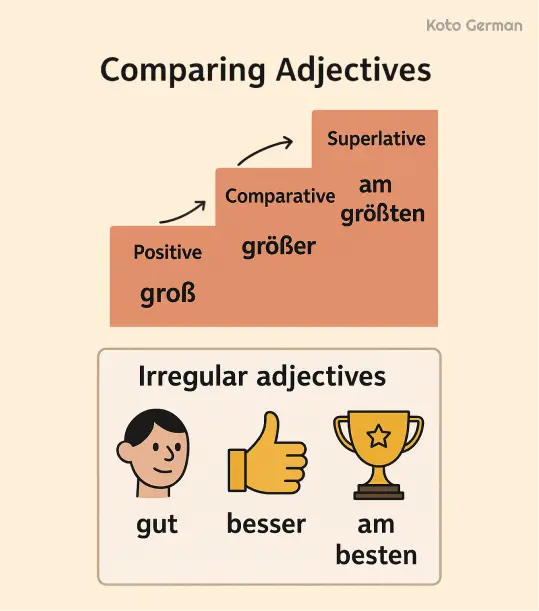

Comparison of Adjectives in German

When you want to draw distinctions in German, adjectives are your best friend. They let you express qualities in stages: first the simple statement, then a step up to compare, and finally the extreme. These three stages are traditionally named the positive, comparative, and superlative.

Positive – The Base Form

The positive is the simplest form of an adjective. It states a quality without comparison.

Examples:

Comparative – Adding -er

To show that one thing has a greater degree of a quality than another, German uses the comparative form. Most adjectives simply add -er to the base.

The word als (“than”) introduces the second part of the comparison. The pattern is clear: adjective + -er + als.

Superlative – The Highest Degree

The superlative marks the highest level of a quality. In German, you add -st or -est. Used predicatively, it usually appears with am and ends in -sten. A German adjectives list provides examples of common superlatives for practice.

When adjectives stand before a noun, they take their usual endings: der aufregendste Tag (the most exciting day).

Irregular Forms

Not every adjective plays by the rules. Some of the common ones are irregular in shape.

Examples in sentences:

Example in everyday speech:

These dialogues show adjectives in attributive, predicative, comparative and superlative forms in real-life situations.

Comparatives and superlatives give your German variety and impact. You can say a meal was gut, but it’s far more engaging to say it was besser als erwartet or even das beste Essen des Jahres. These small shifts turn plain statements into vivid ones.

Practice a little and the patterns become second nature. Soon you will be saying that today is warmer than yesterday, that a film was more exciting than the book, or that your dog is the fastest in the park.

Comparisons turn flat descriptions into lively expressions. Recognizing the different types of German adjectives, from attributive to predicative and adverbial, enables learners to apply endings and placement correctly in context.

Common Learner Mistakes

Between declensions, endings, and word order, it is easy to drop the ball. Many learners run into the same stumbling blocks, and knowing what they are is the first step to avoiding them.

Let’s look at the three most common pitfalls: mixing declensions, forgetting endings, and translating too literally from English.

Mixing Declensions

German adjectives change their endings depending on whether they follow a definite article (der, die, das), an indefinite article (ein, eine), or stand alone without any article. These systems are called weak, strong, and mixed declension.

|

der großer Hund

|

der große Hund

|

|

ein schöner Auto

|

ein schönes Auto

|

the article carries part of the grammatical information. The adjective only adds what’s missing.

Forgetting Endings

Sometimes learners drop endings entirely, either because they are unsure which one to use or because they think the sentence “sounds fine” without them.

|

Das ist ein klein Haus.

|

Das ist ein kleines Haus.

|

|

Ich habe eine neu Tasche gekauft.

|

Ich habe eine neue Tasche gekauft.

|

Direct Translation from English

Adjectives in German can also obey an entirely different set of rules than those in English. Understanding and straight translation may produce strange clauses.

|

Mein Freund ist interessanter in Musik.

|

Mein Freund interessiert sich mehr für Musik.

|

|

Sie ist sehr sympathisch zu mir.

|

Sie ist sehr nett zu mir.

|

German also loves to put the verb second, no matter what starts the sentence. Forget that rule, and the whole structure wobbles.

Mistakes are natural stepping stones in learning German, but some errors can become bad habits if left unchecked. Pay special attention to adjective endings, resist the urge to translate directly from English, and keep word order rules close at hand. Over time, what once felt like juggling flaming torches will become a smooth performance.

Enjoy personalized learning!

Get Some Practice In

Getting comfortable with German adjectives takes practice. Test yourself here and see how well you can spot the correct endings and forms.

Tips to Learn and Practice

The key to adjective endings is regular and constant practice and effective ways of noting them. Through easy tips and tools, you can instill muscle memory in the patterns until they become automatic.

-

Memorization strategies that stick

Associate adjective declensions with real-life examples rather than memorizing long charts. Using German adjectives to describe a person in context makes them easier to remember. At a bakery in Berlin, if you want the fresh bread, you say das frische Brot. Ordering ein frisches Brötchen shows how endings change with nouns. Linking grammar to everyday objects improves recall.

Another trick is to anchor endings with emotions. Eine schöne Blume works well in real life. If you buy flowers for a friend, add a small note with this phrase. Linking the word to a personal experience helps the grammar stick.

-

Use of flashcards, charts, and visual aids

Flashcards remain a learner’s best friend. On one side, write a phrase like the red car and on the other, das rote Auto. Mix in tricky gender changes, such as der rote Apfel, die rote Rose, and das rote Auto. Shuffle them daily to keep your brain alert.

Color coding also helps. Use three colors: blue for masculine, red for feminine, and green for neuter. Build a chart of endings where colors highlight patterns. When your brain sees -er in blue, -e in red, and -es in green, the associations speed up recall.

Visual learners can sketch little doodles. For eine kleine Katze, draw a tiny cat next to the phrase. For ein großer Hund, draw a large dog. The sillier your images, the more likely they are to stick.

-

Real-life practice examples

Language lives in conversations, not textbooks. Next time you’re cooking, describe ingredients aloud: der kalte Saft, die heiße Suppe. When shopping online, read product descriptions and notice German descriptive words’ endings: eine schwarze Jacke (a black jacket), ein bequemes Sofa (a comfortable sofa).

Role-play daily scenarios. Pretend you are renting an apartment in Munich and need to describe it: eine helle Wohnung mit einem großen Balkon (a bright apartment with a big balcony). This not only reinforces endings but also prepares you for practical situations.

For visual learners, YouTube channels like Learn German with Anja or Easy German provide engaging explanations with real street interviews. If you prefer structured grammar drills, Clozemaster is excellent because it drops adjective endings into full sentences, training you to see them in context.

Conclusion

Adjectives in German are essential for clear and precise communication. Descriptions of people, objects, and actions become correct with knowing their forms, their place in the sentence and the principles of strong, weak, and mixed declensions.

Language becomes more expressive with positive, comparative, and superlative comparisons and the knowledge of the mistakes increases the accuracy. Real-life related techniques, including connecting adjectives to common scenarios and flash cards or exercises enhance the learning process.

With regular practice, German adjectives become intuitive, allowing learners to speak and write with confidence.

How do I know which adjective ending to use?

Adjective endings depend on three things: the gender of the noun, the case (nominative, accusative, dative, genitive), and the type of article (definite, indefinite, or no article). Once you know these, the endings follow predictable patterns.

Strong declension is used when there is no article or a “minimal” article, so the adjective carries the main grammatical information. Weak declension is used after definite articles like der, die, das, because the article already indicates gender, case, and number.

Yes. Masculine, feminine, neuter, and plural nouns each have specific endings in nominative, accusative, dative, and genitive cases. Correct endings make sentences grammatically correct.

Apply practical techniques: refer endings to real-life context, make up flashcards, draw diagram tables to refer to, practice on short sentences. The patterns are stickier than anything because of repetition and regular usage in context.